Previously, on A Mind Occasionally Voyaging:

In a certain sense, it’s because the documentary is so strong that it leaves me just a bit unsatisfied. Because, frankly, I can look up how World War I went. “A Brief History of World War I Only With Martians Instead of Germans,” is merely clever; I find myself much more fascinated by the question, “How does the rest of the twentieth century go if we get Alien Tech in 1918?”

Unfortunately, that’s not a question that particularly interests The Great Martian War. Fortunately, I’ve got a bunch of adaptations left to go…

It is June 28, 1914. Yesterday, boxer Jack Johnson won by decision after 20 rounds with Frank Moran in Paris, retaining the World Heavyweight title. He’d eventually lose it to Jess Willard by knockout in Havana the following year. Manchester, NH is rebuilding after a fire downtown. The 23-part serial The Million Dollar Mystery starring Florence La Badie has recently opened in theaters, as has Cecil B. DeMille’s The Only Son, and an adaptation of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. Edgar Rice Burroughs’s first Tarzan novel, Tarzan of the Apes has just been published, as has Baum’s Tik-Tok of Oz. Speaker of the House Champ Clark vows to vote in favor of women’s suffrage when it’s put to vote in Missouri. The referendum will fail in November, amid fears that female voters will push for prohibition, based on the fact that this is pretty much exactly what happens. Missouri’s legislature will grant women the vote late in 1919, which won’t make a lick of difference because the 20th amendment will give it to them anyway before the next election. A time-traveler from the future (I assume, since the idea of both advertorials and anti-vaxxers being native to the 1910s makes me sad) posts an advertorial in the New York Tribune claiming that vaccination is more dangerous than smallpox and tetanus. Teddy Roosevelt refuses to follow his doctor’s advice and give up politics for four months’ bed-rest to treat his malaria, though he’ll relent the next day and agree to take a day off. The Aquitania, Ruritania and Lusitania are all departing New York in the next month on round-the-world trips starting at $474.83.

In Sarajevo, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the throne of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, is assassinated by Yugoslav Nationalist Gavrilo Princip. Through a series of confusing, ill-conceived and boring mutual defense pacts, this leads to Germany invading France.

The United States, of course, remains neutral, since they’re far more concerned with preparing for the immanent return of invaders from Mars.

Some time in the first quarter of 2012, I managed to get the script that automagically makes newly released movie trailers appear in my mythtv working, and it dutifully informed me that there was an animated film coming out that I probably wouldn’t be interested in — some kind of dieselpunk alternate-universe war film that looked like it was pretty much World War I with mecha. I like me some giant robots, don’t get me wrong, but I’m not a huge fan or war films per se. Or dieselpunk. I’d probably have skipped this one, but then it showed the title. War of the Worlds: Goliath.

So I guess I’m in. Goliath is a 2012 animated film produced and directed by Joe Pearson (It’s kinda weird how the name ‘Pearson’ keeps coming up in reference to War of the Worlds…), set during World War I in a world where the events of the HG Wells novel took place in 1899. There’s an obvious parallel to The Great Martian War, but here, World War I itself happens the historical way (at first), with the alien invasion as backstory. War of the Worlds: Goliath, therefore is very much the thing I said I’d have preferred to see. Sorta.

Goliath is also, oddly enough, a bit of a reunion for the cast of Highlander the Series: the voice cast includes Jim Byrnes (Joe Dawson), Elizabeth Gracen (Amanda), Peter Wingfield (Methos) and Adrian Paul (Duncan MacLeod) remember that name. For that matter, screenwriter David Abramowitz was the supervising producer for Highlander the Series and its spin-off Highlander: The Raven. Joe Pearson, whose work has been entirely in animation, isn’t connected to the Highlander TV series directly, but he did work with Abramowitz on the 2007 anime Highlander:The Search for Vengeance.

We’re treated to a sepia-colored montage of life in 1899 intercut with Martian spaceships approaching the Earth as Luka Kuncevic gives us an arrangement of Jeff Wayne’s “Forever Autumn” (Best known for its cover by Justin Hayward for Wayne’s musical adaptation of War of the Worlds, which we’ll talk about eventually) with so much autotuning it sounds like a cyberman is singing it. I mean, it’s clearly intentional; for some reason Kuncevic thought that sounding like a mid-70s robot would make a 1969 Lego jingle sound more apropos to the turn of the century. A longer version plays over the end credits, and at least the electric guitar part is nice.

Post-credits, we open in Leeds, in 1899, where young Eric Wells (Because it’s contractually required for 2 out of 3 War of the Worlds adaptations to name a character after HG Wells) gets his parents killed by panicking in the face of a Martian tripod rather than running for cover. I know that’s putting it bluntly, but this movie is not really big on subtlety. And besides, I have seen exactly this setup about a hundred million times.  Future-hero is confronted by a powerful enemy as a child, panics, dads rushes back to save him and is killed. This haunts the kid his entire life and will be the specter of self-doubt he must overcome in order to unlock his full potential and avenge his parents when the villains return. It’s the backstory for Wonder-Red in The Wonderful 101. It’s the backstory for Simba in The Lion King. It’s the backstory for Inigo Montoya in The Princess Bride. It’s the backstory for Samus Aran in Metroid. Hell, it’s the backstory for the Goddamned Batman. It is even the backstory for Captain Power. I’m not saying it’s a bad trope per se, but the depths of it are pretty well plumbed out by now, especially if you’re not going to give us any real payoff for it. Also, the deaths are needlessly gruesome, showing their flesh burn away and their skeletons and viscera twist as they are reduced to ash. That’s going to be a recurring motif; most battles have at least one money shot of someone getting vaporized but good.

Future-hero is confronted by a powerful enemy as a child, panics, dads rushes back to save him and is killed. This haunts the kid his entire life and will be the specter of self-doubt he must overcome in order to unlock his full potential and avenge his parents when the villains return. It’s the backstory for Wonder-Red in The Wonderful 101. It’s the backstory for Simba in The Lion King. It’s the backstory for Inigo Montoya in The Princess Bride. It’s the backstory for Samus Aran in Metroid. Hell, it’s the backstory for the Goddamned Batman. It is even the backstory for Captain Power. I’m not saying it’s a bad trope per se, but the depths of it are pretty well plumbed out by now, especially if you’re not going to give us any real payoff for it. Also, the deaths are needlessly gruesome, showing their flesh burn away and their skeletons and viscera twist as they are reduced to ash. That’s going to be a recurring motif; most battles have at least one money shot of someone getting vaporized but good.

The 1899 tripod looks to have taken some inspiration from Henrique Alves Corrêa’s illustrations

The 1899 tripod looks to have taken some inspiration from Henrique Alves Corrêa’s illustrations for the 1906 French edition of the novel. The general shape is somewhat similar to a water tower, with a barrel-shaped body and wide-brimmed roof on long, stilt-like legs. There’s two large windows in the front, positioned like eyes. A cylindrical extension projects forward just below the main body, which you’d think was the heat ray, but the heat-ray is a separate unit, slung lower, in a position that kind of makes it look like the tripod’s naughty bits. Actually, the curve of the roof strongly resembles a Brodie Helmet, and when combined with the large window-eyes and the cylindrical extension, the combined effect is to make the tripod’s main body look uncannily like the head of a World War I soldier, kitted out for the trenches in helmet and gas mask. My assumption is that this is intentional given the premise, but there’s some things later on that make that seem weird. The tripod, as would be expected, conveniently drops dead before it can fire its green heat ray a third time and kill our nominal protagonist before the story even gets started.

for the 1906 French edition of the novel. The general shape is somewhat similar to a water tower, with a barrel-shaped body and wide-brimmed roof on long, stilt-like legs. There’s two large windows in the front, positioned like eyes. A cylindrical extension projects forward just below the main body, which you’d think was the heat ray, but the heat-ray is a separate unit, slung lower, in a position that kind of makes it look like the tripod’s naughty bits. Actually, the curve of the roof strongly resembles a Brodie Helmet, and when combined with the large window-eyes and the cylindrical extension, the combined effect is to make the tripod’s main body look uncannily like the head of a World War I soldier, kitted out for the trenches in helmet and gas mask. My assumption is that this is intentional given the premise, but there’s some things later on that make that seem weird. The tripod, as would be expected, conveniently drops dead before it can fire its green heat ray a third time and kill our nominal protagonist before the story even gets started.

The animation in Goliath is interesting. Like I said back in Gandahar, I’m no expert on animation. Goliath was animated in Malaysia, which has a pretty robust animation industry, but not one I have any other experience with. The thing it looks the most like is the 1990s DCAU stuff — the animated Batman and Superman in particular. Everyone’s got these ridiculous comic-book proportions with gigantic chests, Lenoesque chins and small waists. But there’s also elements that remind me a lot of Aeon Flux: anything gory, like the deaths of Eric’s parents, but there’s also something about the character of Jennifer Carter that reminds me a lot of Peter Chung’s work. The film is 3D computer animated, and the cel shading here is first rate; I’d at first assumed it was a hybrid animation style, using CGI for the mecha and traditional animation for people.The animation is absolutely fantastic. I won’t call it “beautiful”, though, because an awful lot of it is very deliberately ugly.

There’s also a whole lot of detail in the backgrounds, such as the New York City of 1914, where our story resumes. One obvious downside to setting a story in New York City in 1914 is that it doesn’t actually look that much like New York City: you’re missing all that fantastic Gothic Revival and Art Deco stuff. Pretty much the only things you’ll see in Goliath‘s New York that really shouts “New York” are the Flatiron building and something I’m not going to mention yet for dramatic effect. Instead of the familiar skyscrapers of modern New York, the city is instead decorated with numerous statues memorializing the Martian invasion, which all tend to depict humanity as having a greater hand in the defeat than it did, soldiers with heavy arms standing astride felled tripods or skewering squid-like Martians. New York is an exceedingly smoky place. For that matter, just about everything in this movie belches huge amounts of diesel exhaust, which is presumably historically accurate, but is strangely at odds with the technological motif.

Eric Wells, now grown into a barrel-chested adult, rides a suspension train that runs down Fifth Avenue to the headquarters of ARES, Earth’s unrealistically ethnically diverse “Allied Resistance Earth Squadron”. ARES is run by Secretary of War Teddy Roosevelt, Russian General Sergei Kushnirov (Who is not a real person, but is played by Rob Middleton, who hasn’t been in anything since the ’80s, but does have one credit I recognized: he played the monster that lived in Dorian’s basement in the first episode of the last season of Blake’s 7), and Nikola Tesla. It’s made up of the best and brightest of the world’s various armies, putting aside things like racism, sexism, or the fact that the world is full of countries which all hate each other. The men and women of ARES put all that nationalism aside to work together in the name of their common humanity. Except for the Germans, who are kind of assholes. Well, mostly. Ace pilot Manfred von Richtofen seems like a mensch, even if he did make a point of showing off by buzzing the train earlier.

Eric Wells, now grown into a barrel-chested adult, rides a suspension train that runs down Fifth Avenue to the headquarters of ARES, Earth’s unrealistically ethnically diverse “Allied Resistance Earth Squadron”. ARES is run by Secretary of War Teddy Roosevelt, Russian General Sergei Kushnirov (Who is not a real person, but is played by Rob Middleton, who hasn’t been in anything since the ’80s, but does have one credit I recognized: he played the monster that lived in Dorian’s basement in the first episode of the last season of Blake’s 7), and Nikola Tesla. It’s made up of the best and brightest of the world’s various armies, putting aside things like racism, sexism, or the fact that the world is full of countries which all hate each other. The men and women of ARES put all that nationalism aside to work together in the name of their common humanity. Except for the Germans, who are kind of assholes. Well, mostly. Ace pilot Manfred von Richtofen seems like a mensch, even if he did make a point of showing off by buzzing the train earlier.

Roosevelt has some troubling news for ARES: Mars is once again in opposition, and Tesla believes he’s detected evidence that the Martians are launching a renewed attack. To make matters worse, half of ARES’ soldiers have been recalled to Europe in anticipation of a war between the great powers over there.

Yes. World War I is still gearing up to happen over in Europe. Now, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve defended works of science fiction for pulling the whole “Aliens invade in the ’70s and yet the ’90s are superficially identical to the ones the viewer lived through,” thing. There’s a lot of people who take issue with the idea that, post-alien-invasion, humanity would get back to their lives rather than instantly evolving into spangly space-clothes wearing Science Fiction Characters, and I don’t think that it necessarily follows that the absolute knowledge of the existence of hostile extraterrestrials would have a huge impact on the day-to-day lives of most people, for the same reason that the discovery that the Earth goes ’round the sun didn’t. During the invasion, yeah, sure, things are very different. But once the Martians are finished dying, the cows still got to be milked and the lawn’s still got to be mowed, and there’s no per se reason — provided that the invasion is done-in-one and there isn’t continuing contact with the aliens — that it wouldn’t be handled exactly the same way as every other kind of large-scale disaster, like an earthquake or a hurricane, that comes out of nowhere, shakes things up, then leaves.

But this still feels wrong. Not that Europe wouldn’t still be itching to get its war on — Europe had been itching to get its war on pretty much continuously for centuries, and it seems hopelessly optimistic to me to assume that Kaiser Wilhelm and Franz Joseph and George V and Raymond Poincaré would all set aside the fact that their countries all hated each other just because there were Martians now. No, that bit I’m okay with — it even sort of works to have this sense that ARES was assembled immediately after the war out of a sudden feeling of a common brotherhood of man and the need for mutual defense, but after a few years, the old rivalries and hatreds resurfaced. Rather, it seems awfully forced that, after the destruction of much of the world’s military and a tenth of its population (Literal decimation!), everyone would be ready in fifteen years. We’ve already seen this is a different world than the real 1914; Eric here is the commander of an ARES tripod, built by Tesla based on his studies of alien tech. Humanity has heat rays and giant mecha. And you’re telling me that Europe had time to put their shattered cities back together and raise a new generation of soldiers to replace the ones lost in the Martian war and build new battle fleets using an entirely new kind of technology (Because seriously, if heat ray-equipped giant mechs are a thing that exists, are you seriously going to start a war without some of your own?), and this didn’t push everyone’s schedule back a few years?

General Kushnirov believes that the key to being prepared for the Martians’ return lies in their new “Achilles-Class” Tripod. Because when you’re building what is, essentially, a tank complicated by the fact that instead of rolling on treads, it has to accomplish the much more difficult feat of walking on legs without falling, you naturally assume it’s a good idea to name it after a guy who is famous for being killed by injuring his ankle. It’s one of the laws of military naming symbolism, like how you have to call your high-altitude craft “Icarus” or your indestructible spaceship “Titanic 2”, or your physics-defying ship “The SS. Fuck you, Newton”.

General Kushnirov believes that the key to being prepared for the Martians’ return lies in their new “Achilles-Class” Tripod. Because when you’re building what is, essentially, a tank complicated by the fact that instead of rolling on treads, it has to accomplish the much more difficult feat of walking on legs without falling, you naturally assume it’s a good idea to name it after a guy who is famous for being killed by injuring his ankle. It’s one of the laws of military naming symbolism, like how you have to call your high-altitude craft “Icarus” or your indestructible spaceship “Titanic 2”, or your physics-defying ship “The SS. Fuck you, Newton”.

Having been established as the main character, command of the first Achilles-class Tripod off the line, dubbed “Goliath”, naturally goes to Eric, on account of his performance in simulations and also because his team meets Haim Saban’s requirements for diversity among a five-man special forces team. The British Wells is accompanied by an American Lieutenant, Jennifer Carter, because the US has female combat troops in 1914 but this complete social upheaval didn’t deter World War I from happening (Remember, in the real world, women in the US don’t have the vote yet); Sergeant Abraham Douglas from Canada, because Canada has desegregated their armed forces by 1914 but this complete social upheaval didn’t deter World War I from happening; Lieutenant Raja Iskandar from British Malaya (Present-day Malaysia, where, as noted, the film was made); and Corporal Patrick O’Brien from Ireland. Wells, of course, is an enlightened Englishman who has no problem serving with a woman, an Irishman, a black guy and a southeast Asian (I mean, I guess it helps that the white British guy is the one who’s in charge), and neither does anyone else. Except the Germans, who are kind of jerks.

Everyone heads down to the local pub before the next day’s war games, where O’Brien tells Roosevelt that he isn’t on speaking terms with his IRA brother and is loyal to the British Crown, then promptly sneaks out to meet his IRA brother to explain that the impending invasion will delay their plans to steal a bunch of heat rays to send back to Ireland for use in terrorism against the British. His brother threatens to kill him if he backs out of the plan, and makes a big point of how he is perfectly willing to screw over humanity in the face of unstoppable Martian invasion if he can sate his desire to kill the English. The brother, by the way, is voiced by Mark Sheppard. I guess after The X-Files, Sliders, Star Trek, Firefly, 24, The Middleman, Battlestar Galactica, Chuck, Warehouse 13, Supernatural and Doctor Who, he reckoned he needed one more sci-fi-cult-franchise to get the free sub.

Back at the bar, the Germans try to start shit. Richtofen unsuccessfully tries to calm things down, and we are almost treated to Teddy Roosevelt getting into a fist fight with the Red Baron.  But things settle down when Kushnirov shows up to deliver the news of Franz Ferdinand’s assassination, and the resulting orders for the European ARES members to pack up and go home. Eric gives just about the most cliched speech in the world, which inexplicably convinces all of ARES to commit treason en masse and stay in New York, Richtofen even asserting, “Deutchland can kiss my ass.”

But things settle down when Kushnirov shows up to deliver the news of Franz Ferdinand’s assassination, and the resulting orders for the European ARES members to pack up and go home. Eric gives just about the most cliched speech in the world, which inexplicably convinces all of ARES to commit treason en masse and stay in New York, Richtofen even asserting, “Deutchland can kiss my ass.”

That night, Eric stays up late tinkering with Goliath, in order that he can have a tender scene with Jennifer, the child of wealth and privilege who ran off and joined the army to get away from her controlling father, so that she can tell him that his parents’ death isn’t his fault and because the movie is shipping these two, even though it can not spare the time away from mech battles to actually sell it. The next morning, a Martian scouting party attacks the war games.  The new tripods are larger and sleeker in design, with more powerful heat rays that can cripple the large Achilles-class or destroy the smaller ARES tripods with a single shot. ARES is victorious against the small force, but the victory comes at a substantial cost.

The new tripods are larger and sleeker in design, with more powerful heat rays that can cripple the large Achilles-class or destroy the smaller ARES tripods with a single shot. ARES is victorious against the small force, but the victory comes at a substantial cost.

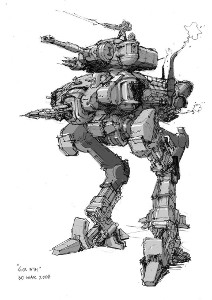

ARES tripods are markedly smaller than their Martian counterparts, and boxier. They look pretty much like tanks with legs, a la Metal Gear. They’re armed with both red-beamed heat rays and more conventional weapons which, as in the novel, can fell a Martian tripod, but only with concentrated fire, a good deal of luck, and a distraction to keep the tripod from incinerating it first. Portable backpack-sized heat rays also exist. General Kushnirov commands a large “leviathan” airship, armed with its own giant wave motion canon dealie which they don’t whip out until the last scene.

After the battle, O’Brien visits his brother, to reiterate that the IRA does not consider an alien invasion a good reason to change their plans. Sean O’Brien declares his brother dead to him, then drops out of the story altogether because this part is boring. The next battle we see is implied to be the next day, but it makes far more sense for it to be some time later. Richtofen defends the leviathan from Martian flying machines while humming Ride of the Valkyries and pulling off maneuvers which, unless Wings 2: Aces High lied to me, aren’t actually possible in a World War I triplane (In their defense, on my second watching, there’s a bit earlier in the movie which suggests that Richtofen’s plane has been retrofitted with something akin to an afterburner).

Goliath is disabled in battle and Eric’s team evacuates. They randomly meet a somewhat deranged militiaman who keeps his wife’s dismembered finger in a pouch around his neck. He leads them to an alien-occupied power plant, then conveniently sacrifices himself as a distraction. They mention in passing that human power plants are based on salvaged alien tech, which is odd since we have not seen a damned thing that doesn’t run on fossil fuels.  They rescue some captured humans from the Martian larder, though not before we get to see one of the prisoners get deep-throated to death by an alien bendy-straw. There’s an interesting level of effort here to keep the aliens themselves close to the book: physically, they’re sort of squid-like, enormous, leathery heads with exposed brains, a beak-like mouth, no body to speak of, living off the blood of their victims.

They rescue some captured humans from the Martian larder, though not before we get to see one of the prisoners get deep-throated to death by an alien bendy-straw. There’s an interesting level of effort here to keep the aliens themselves close to the book: physically, they’re sort of squid-like, enormous, leathery heads with exposed brains, a beak-like mouth, no body to speak of, living off the blood of their victims.

The power plant has been converted to a factory where the Martians are building a kind of dreadnought, a large flying wing that I assume is an homage to the pointless inclusion of Northrup YB-49 stock footage as a bit of spectacle in George Pal’s 1953 film adaptation.  Everyone is shocked by it, and it’s clearly meant to be the first time they’ve seen this terrifying weapon. Which is odd, since they were mentioned in passing a few scenes earlier when talking about enemy troop movements. They blow up the plant and the flying wing therein, but it turns out that this is all part of an elaborate Martian feint, to draw the bulk of ARES out west while the Martian armada converges on Manhattan. Which technically makes the whole scene with them risking life and limb to destroy the Martian Wing pointless, but at least Eric gets laid for his trouble, as Jennifer jumps him later that night while he’s repairing Goliath.

Everyone is shocked by it, and it’s clearly meant to be the first time they’ve seen this terrifying weapon. Which is odd, since they were mentioned in passing a few scenes earlier when talking about enemy troop movements. They blow up the plant and the flying wing therein, but it turns out that this is all part of an elaborate Martian feint, to draw the bulk of ARES out west while the Martian armada converges on Manhattan. Which technically makes the whole scene with them risking life and limb to destroy the Martian Wing pointless, but at least Eric gets laid for his trouble, as Jennifer jumps him later that night while he’s repairing Goliath.

And then, weirdly, the main characters kinda drop out of the story. Not entirely — they’ll turn up for a line or two — but once the action switches to the battle in Manhattan, they’re really no longer our main characters.  Roosevelt’s defense of ARES HQ becomes the focus of the story now, and the whole rest of the film is just balls-to-the-wall action. Teddy Roosevelt brandishing a machine gun, shooting down Martian fighters; two ARES airships pulling out their giant heat-rays to attack a one of those Martian Wings (which knocks the Statue of Liberty off her pedestal, in accordance with the regulations mandating the destruction of the Statue of Liberty by any aliens and/or kaiju who attack New York City in a movie); a zepplin chase through the streets of Manhattan. The leviathan is damaged, and a lieutenant we’ve never seen before starts to fall toward the conflagration below. Kushnirov catches him and struggles to pull him back up, but as the general is the only person who could get to the controls to right the craft, the younger officer deliberately pulls free and falls to his death, but not before revealing to the audience that he’s Kushnirov’s son and only remaining family after the last war. Kushnirov wins the battle by crashing the leviathan into the Martian ship.

Roosevelt’s defense of ARES HQ becomes the focus of the story now, and the whole rest of the film is just balls-to-the-wall action. Teddy Roosevelt brandishing a machine gun, shooting down Martian fighters; two ARES airships pulling out their giant heat-rays to attack a one of those Martian Wings (which knocks the Statue of Liberty off her pedestal, in accordance with the regulations mandating the destruction of the Statue of Liberty by any aliens and/or kaiju who attack New York City in a movie); a zepplin chase through the streets of Manhattan. The leviathan is damaged, and a lieutenant we’ve never seen before starts to fall toward the conflagration below. Kushnirov catches him and struggles to pull him back up, but as the general is the only person who could get to the controls to right the craft, the younger officer deliberately pulls free and falls to his death, but not before revealing to the audience that he’s Kushnirov’s son and only remaining family after the last war. Kushnirov wins the battle by crashing the leviathan into the Martian ship.

With the battle, but not the war, won, we close on Secretary Roosevelt giving a speech to the survivors in the ruins of ARES HQ, promising vengeance for their fallen comrades and to eventually take the fight to Mars.

War of the Worlds: Goliath is… Weird.

Goliath is also bizarrely gruesome. They love these scenes of soldiers being shredded by heat rays. Even the Martians get a little of it: Raja dispatches one with his knife and is left covered in glowing green blood (Remember this). And when the leviathan crashes into the Wing at the end, its prowl smashes through the windshield and impales the pilot through the eye. I can not fault this movie visually. But that is just about the only thing I can’t fault. The plot is… Not so much a “plot” as a concept. The characters have some promise, but they don’t spend any time with them. I appreciate the attempt to have the characters be more than just ticking off boxes in an ethnic diversity matrix, but it doesn’t amount to anything: O’Brien’s Fenian sympathies boil down to two scenes of Adrian Paul and Mark Sheppard arguing which aren’t connected to anything else in the movie at all. Jennifer’s issues with her father are mentioned exactly twice. The extent of the characterization for Abraham Douglas (whose name sounds like it was generated by the algorithm they used to name black sitcom characters in the ’70s) is for him to mention that he’s got two daughters he’s worried about. We see the tail end of Raja performing the Salat, and there’s a scene that should go somewhere there when O’Brien and Raja talk about their shared status — they’re both from cultures that are unwillingly under British rule. But it doesn’t go anywhere. There’s no real direction to the plot, it’s just a bunch of seemingly random incidents that all take place under the blanket of this war.

I came into this from the question, “What sort of world would we get a few decades after the Martians invade.” The answer they give us is… incomplete. It is a different world — they’ve got tripedal tanks and suspension railways and the Statue of Liberty has a sword. But it’s just a motif, really. A little visual flavor. Europe’s still about to explode into a profoundly stupid war for profoundly stupid reasons. All the same people are in all the same places doing all the same things (Except for Roosevelt, who apparently did not seek a second term in this universe). There’s potential for something in the fact that Eric Wells commands an racially integrated coed unit, but no one ever says anything about it or takes more than a cursory glance at the implications of that.

I came into this from the question, “What sort of world would we get a few decades after the Martians invade.” The answer they give us is… incomplete. It is a different world — they’ve got tripedal tanks and suspension railways and the Statue of Liberty has a sword. But it’s just a motif, really. A little visual flavor. Europe’s still about to explode into a profoundly stupid war for profoundly stupid reasons. All the same people are in all the same places doing all the same things (Except for Roosevelt, who apparently did not seek a second term in this universe). There’s potential for something in the fact that Eric Wells commands an racially integrated coed unit, but no one ever says anything about it or takes more than a cursory glance at the implications of that.

You know what it feels like? An abridgment. This feels like when a long-running anime series gets condensed down to a two-hour OVA. In fact, it feels more than anything I can think of like the Family Home Entertainment VHS abridgments of Robotech, that would grind six episodes of the cartoon down to a 45-minute video. There’s so much promise here, but it’s like we’re only seeing the highlights reel. Characters basically enter, give us one scene to establish themselves, then leave. There should be more. Like hours more to cover the scope of what we’re seeing. We should see that whole relationship between Patrick and Sean O’Brien (And there should be a recurring threat from Sean’s partner who wants to kill Patrick outright for his betrayal). We should see a relationship between Jennifer and Eric, something more than just “It’s hinted he likes her in scene 4 and then she out of nowhere decides to bone him inside Goliath’s cockpit in scene 8”. Those prisoners they rescue from the power plant — they should go somewhere. Probably, they should end up having to stay on the leviathan for some length of time. There should be skirmishes and minor battles with the Martians. We should see Tesla studying bits of salvaged Martian technology. There should be some kind of buildup and backstory with Kushnirov and his son, rather than plot-bombing us with his son’s identity a second before you kill him. And the decision to make the climax of the movie center around the battle between the leviathan and the Martian Wing, rather than, y’know, Goliath is utterly incomprehensible; it’s a fine scene, but it shouldn’t be the climax — it should happen about five minutes before the climax, with their sacrifice buying the actual main characters their chance to deal the finishing blow to the attacking army. This movie feels incomplete: it’s insubstantial, and yet you can almost feel like there’s something substantial this has been carved out of.

Actually, Robotech. Hm. You know? This movie feels an awful lot like Robotech. Joe Pearson was a personal friend of Carl Macek, who converted two largely unrelated and one totally unrelated anime into the original three-season Robotech saga. They’d worked together in the ’80s (Not on Robotech, though Pearson does get a “special thanks” credit in 2013’s Robotech: Love Live Alive, which I briefly mentioned in relation to the Captain Power Training Videos). There are definitely parallels. An international force defending Earth using new technology developed from studying salvaged alien tech? The big ship with the big honkin’ gun being commanded by a Russian? I’m sure you’ll find parallels to lots of Mecha anime and it just happens that Robotech is the one I’m most familiar with. Goliath is very straightforwardly “Let’s do a standard ’80s style Giant Mecha anime only set during World War I as a sequel to War of the Worlds.” I would not mind watching a Goliath TV series. But as a movie, there’s very little here to bring me back. Not unlike The Great Martian War, it’s what they didn’t show me that interests me more than what they did.

- War of the Worlds: Goliath is available on DVD, Blu-Ray and streaming video from amazon.com

I think it’s a bit of a pleasant sign of the times we live in that they made the effort to do a little bit to correct the extent to which the indigenous peoples of the Americas are represented in things like 20th century history, especially in a context that implies that his work had been largely overlooked precisely because no one was expecting a major breakthrough to come from a First Nations enlisted soldier. That his discoveries are specifically linked to the translation of the alien language may be an homage to the Navajo Code Talkers, though it that’s true, it’s maybe just a bit uncomfortable that they’ve conflated the country, tribe, and which war it was. But still, props and all.

I think it’s a bit of a pleasant sign of the times we live in that they made the effort to do a little bit to correct the extent to which the indigenous peoples of the Americas are represented in things like 20th century history, especially in a context that implies that his work had been largely overlooked precisely because no one was expecting a major breakthrough to come from a First Nations enlisted soldier. That his discoveries are specifically linked to the translation of the alien language may be an homage to the Navajo Code Talkers, though it that’s true, it’s maybe just a bit uncomfortable that they’ve conflated the country, tribe, and which war it was. But still, props and all. The most accurate summation of why World War I happened I’ve ever heard comes from Edmund Blackadder: it was too much effort not to have a war.

The most accurate summation of why World War I happened I’ve ever heard comes from Edmund Blackadder: it was too much effort not to have a war. The “heat ray” is described as a “slow-firing energy cannon”, and, like their 1953 counterparts, the Herons are protected by an “energy shield”. There’s a rare hint at how this world’s 2013 has diverged from our own: the shields are described as “The first introduction we had to the many uses of dark energy particles.” The Herons are a bit similar in design to Warwick Goble’s original illustrations for the serial run of The War of the Worlds (Which Wells himself personally disowned and criticized in a passage he added when the book was published in novel form). The “black smoke” is a function of the Herons too, a “toxic cloud” that surrounds the machines. The effectiveness of it is greatly scaled down here, though, making it much more similar to the chemical weapons that were introduced in the real-world Great War. Gas masks prove effective against it, though interviewee Jock Donnelly describes the sense of dreadful isolation that comes with that sort of fighting.

The “heat ray” is described as a “slow-firing energy cannon”, and, like their 1953 counterparts, the Herons are protected by an “energy shield”. There’s a rare hint at how this world’s 2013 has diverged from our own: the shields are described as “The first introduction we had to the many uses of dark energy particles.” The Herons are a bit similar in design to Warwick Goble’s original illustrations for the serial run of The War of the Worlds (Which Wells himself personally disowned and criticized in a passage he added when the book was published in novel form). The “black smoke” is a function of the Herons too, a “toxic cloud” that surrounds the machines. The effectiveness of it is greatly scaled down here, though, making it much more similar to the chemical weapons that were introduced in the real-world Great War. Gas masks prove effective against it, though interviewee Jock Donnelly describes the sense of dreadful isolation that comes with that sort of fighting. This is another thing that The Great Martian War does well. The interview footage is really convincing. In fact, if you told me some of it was actual interviews with real World War I veterans — the bits where they’re just speaking about the horrors of war or conditions in the trenches without anything specific about aliens — I’d believe you. I’d be pissed that they’d misrepresented the real testimony of real people’s real suffering for this show, but I’d believe you. (It’s not. I checked. The interview footage is all done with actors). What sells it is the audiovisual texture. Remember, this is purporting to be a documentary made a century after the fact: hardly anyone who was alive in 1913 would be available for interview in 2013, and certainly no one who was old enough to have served in combat (The last known World War I veteran died in 2012), so this is all archive footage dated from the ’60s to the ’90s. The sound is flat. The video is grainy — and it’s grainy in different ways. Interviews dated to the early ’80s have film grain, and those from the ’90s have VHS artifacts. Some of it is in 4:3. Other parts are widescreen but have that slightly-wrong look of having been cropped and enlarged. The colors are either oversaturated or faded depending on the vintage. The only interview footage that looks really inauthentic is of an interview with author Nerys Vaughn in the 1960s, and even there, it looks quite a lot like the “reenacted” interviews they sometimes attach to this sort of documentary.

This is another thing that The Great Martian War does well. The interview footage is really convincing. In fact, if you told me some of it was actual interviews with real World War I veterans — the bits where they’re just speaking about the horrors of war or conditions in the trenches without anything specific about aliens — I’d believe you. I’d be pissed that they’d misrepresented the real testimony of real people’s real suffering for this show, but I’d believe you. (It’s not. I checked. The interview footage is all done with actors). What sells it is the audiovisual texture. Remember, this is purporting to be a documentary made a century after the fact: hardly anyone who was alive in 1913 would be available for interview in 2013, and certainly no one who was old enough to have served in combat (The last known World War I veteran died in 2012), so this is all archive footage dated from the ’60s to the ’90s. The sound is flat. The video is grainy — and it’s grainy in different ways. Interviews dated to the early ’80s have film grain, and those from the ’90s have VHS artifacts. Some of it is in 4:3. Other parts are widescreen but have that slightly-wrong look of having been cropped and enlarged. The colors are either oversaturated or faded depending on the vintage. The only interview footage that looks really inauthentic is of an interview with author Nerys Vaughn in the 1960s, and even there, it looks quite a lot like the “reenacted” interviews they sometimes attach to this sort of documentary. The Great Martian War, though, wants a “whole” war story, so it takes the rare step of changing it up a bit. Like the original, there are four distinct types of Martian war machine, though they’re entirely distinct from those in the novel. The second type of machine introduced is the “Iron Spider”, a smaller form of tripod that acts as the Martian infantry. It’s a clever way to divvy things up: between the original and its many famous adaptations, there’s a whole assortment of traits associated with the Martian war machines that are kind of a clusterfrak when put together, so here, they divide up the popular tripod traits between the two different kinds of machine. The Spiders are smaller and far more agile than the Herons, whose size honestly makes them look kind of awkwardly matched against human infantry. The primary purpose of the Herons, it seems, is not to kill humans in large numbers directly, but rather to destroy cover and force soldiers out into the open, where the agile Spiders, roughly the size of a modern tank and twice as tall, could dispatch them with “ribbons of death”, highly articulated tentacles that are extremely accurate to the tentacle appendages Wells described on the fighting machines, prefiguring modern inventions like electroactive polymers and muscle-wire.

The Great Martian War, though, wants a “whole” war story, so it takes the rare step of changing it up a bit. Like the original, there are four distinct types of Martian war machine, though they’re entirely distinct from those in the novel. The second type of machine introduced is the “Iron Spider”, a smaller form of tripod that acts as the Martian infantry. It’s a clever way to divvy things up: between the original and its many famous adaptations, there’s a whole assortment of traits associated with the Martian war machines that are kind of a clusterfrak when put together, so here, they divide up the popular tripod traits between the two different kinds of machine. The Spiders are smaller and far more agile than the Herons, whose size honestly makes them look kind of awkwardly matched against human infantry. The primary purpose of the Herons, it seems, is not to kill humans in large numbers directly, but rather to destroy cover and force soldiers out into the open, where the agile Spiders, roughly the size of a modern tank and twice as tall, could dispatch them with “ribbons of death”, highly articulated tentacles that are extremely accurate to the tentacle appendages Wells described on the fighting machines, prefiguring modern inventions like electroactive polymers and muscle-wire.

The historical Aquitania would serve in both World Wars as a troop transport and hospital ship, and operate in peacetime as a cruise ship until

The historical Aquitania would serve in both World Wars as a troop transport and hospital ship, and operate in peacetime as a cruise ship until

Fortunately for Europe, the Martians inexplicably attack a group of American destroyers. Or do they? The interviewed historian points out that there’s no hard evidence of Martian presence in the Gulf of Mexico, and notes that Allied U-Boats had the range to have done it themselves, coyly hinting that it may have been a false flag by the Allies to trick the Americans into the war. Woodrow Wilson resigns in disgrace, and for some reason — they talk around it, but it kinda sounds like a coup — this makes Teddy Roosevelt president and the US enters the war proper.

Fortunately for Europe, the Martians inexplicably attack a group of American destroyers. Or do they? The interviewed historian points out that there’s no hard evidence of Martian presence in the Gulf of Mexico, and notes that Allied U-Boats had the range to have done it themselves, coyly hinting that it may have been a false flag by the Allies to trick the Americans into the war. Woodrow Wilson resigns in disgrace, and for some reason — they talk around it, but it kinda sounds like a coup — this makes Teddy Roosevelt president and the US enters the war proper.

In a rare attempt to actually show us something, Tiffany has her cameraman do the world’s least convincing transition, sweeping the camera upward as they do a quick dissolve to some stock footage of three F-14s, that Tiffany thinks are all one plane. While teleporting back to Mojave, she also had time to interview an official, who, off the record, gave her the news tidbit that there was “some kind of activity” in the pit. This is about the fourth time they’ve acted as if declaring that “something happened” without further elaboration is actually news.

In a rare attempt to actually show us something, Tiffany has her cameraman do the world’s least convincing transition, sweeping the camera upward as they do a quick dissolve to some stock footage of three F-14s, that Tiffany thinks are all one plane. While teleporting back to Mojave, she also had time to interview an official, who, off the record, gave her the news tidbit that there was “some kind of activity” in the pit. This is about the fourth time they’ve acted as if declaring that “something happened” without further elaboration is actually news.